The Eagle Creek Writers Group is back!

What: meeting for conversation and critique

When: Wednesday, April 5, 6:30 p.m. EDT

Where: Chaotic Good, 454 S. Broadway, Suite 160 (corner of Broadway and Oliver Lewis) https://www.chaoticgoodlex.com/

The Eagle Creek Writers Group is back!

What: meeting for conversation and critique

When: Wednesday, April 5, 6:30 p.m. EDT

Where: Chaotic Good, 454 S. Broadway, Suite 160 (corner of Broadway and Oliver Lewis) https://www.chaoticgoodlex.com/

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged meetings | 2 Comments »

The Eagle Creek Writers Group will meet for conversation and critique at 6:30 p.m., March 15, 2023, at Panera Bread on Richmond Road, Lexington.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged meetings | Leave a Comment »

What: Informal meeting for chat or critique

When: 6:30 p.m. EST, March 1, 2023

Where: Panera Bread on Richmond Rd. at New Circle, Lexington

Posted in Member news | Tagged critique, meetings | Leave a Comment »

Get ready, prose writers: the poets are about to pass the pen to you!

Get ready, prose writers: the poets are about to pass the pen to you!

May is Short Story Month!

Read all about it here: http://shortstorymonth.com/about/

Find interviews, prompts, contests, challenges, and other juicy tidbits here: https://storyaday.org/

If you need encouragement, Ann R. Allen offers 13 reasons why you should write a short story this month: https://annerallen.com/2015/05/13-reasons-why-you-should-write-shor/

And if you are all written out for the nonce (I feel you, fellow poets!) the Emerging Writers Network has a list of 74 short story collections that were slated for publication this year: https://emergingwriters.typepad.com/emerging_writers_network/short_story_month/. Some of these will no doubt be in your local library.

My own recommendation for a short story collection is Tom Hanks’ Uncommon Type, which I picked up earlier this year at our very own Eastside Branch. The stories are quite different from one another, but I enjoyed them very much, not the least because I could hear Hanks’ voice in my head as I read.

If new fiction just isn’t your cup of tea, break out something more classic:

Mark Twain, Marge Piercy, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Virginia Woolf, Ray Bradbury, Margaret Atwood, Ernest Hemingway, James Baldwin, Shirley Jackson, Saki, Doris Lessing, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Katherine Anne Porter, Jack London, P.L. Travers, Stephen King, Ursula LeGuin, Kazuo Ishiguro . . .

There are 31 days in May. Make sure you set aside part of at least one of them for a short story.

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Short Story Month | Leave a Comment »

“Notes of encouragement to new writers” is the theme this month at Smack Dab in the Middle, a blog by/for/about writing for middle grade students that — surprise! — has lots of great advice for writers everywhere. Sunday’s post by Chris Tebbetts makes some wonderful observations about showing up: for the work, for the community, and for ourselves.

Here are some of my favorite bits:

“In my experience, the people who make it in publishing are the ones who manage to give sufficient energy to both halves of that dichotomy [the art and the business of writing].”

“I was showing up, and showing up, and showing up, not so I could score a distinct win every time, but so that I could eventually find myself in the right place at the right time.”

“. . . persistence is everything in publishing. It’s also the one thing you can control.. . .”

Give it a read and take away whatever encourages you.

http://smack-dab-in-the-middle.blogspot.com/2019/04/showing-upand-upand-up.html

Posted in Craft | Tagged Chris Tebbetts, Smack Dab in the Middle, writing advice | Leave a Comment »

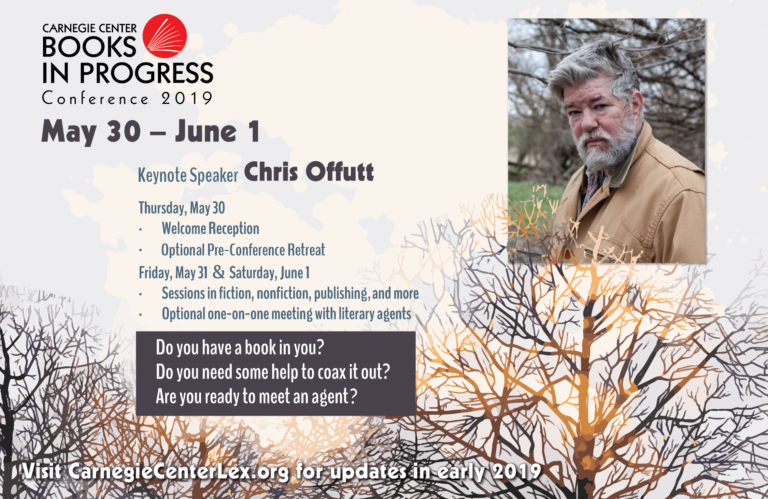

Today is the last day to get the lower early-bird rate for the Carnegie Center’s 2019 Books in Progress Conference. For full information and to register, visit

http://carnegiecenterlex.org/event/books-in-progess-conference-2019/

Posted in Uncategorized | Tagged Books in Progress Conference, Carnegie Center for Literacy and Learning, writers' conferences | Leave a Comment »

Beth Nguyen’s thoughtful article on writing workshops appeared at Literary Hub this week. She describes how her approach to critique changed when she began teaching nonfiction, work in which the integration of context and author with the text is more obvious than is sometimes the case with other genres.

Especially interesting to me was the way this reshaped feedback (emphasis mine):

The workshoppers, in turn, are asked to do less prescribing (I want to see more of this; I want this or that to happen; I didn’t want that character to be here) and more questioning. Why did you use first-person? How important is the sister character supposed to be? Instead of a typical old-school workshop comment such as “I want to see more about the mother,” there’s a question: “We don’t see much about the mother—how important of a character is she?” The former is a demand; the latter is an opening.

Even in settings where time or other constraints make full-blown conversation among participants impractical, feedback phrased this way invites reflection rather than defense. We best serve one another when our comments encourage thinking about the art and process of writing, from choices and techniques to audience and intention.

Implementing this in our own critique practices will require some adjustments, for both respondents and authors. But it seems like work worth doing if it allows each writer “to leave feeling heard and feeling motivated to keep working and revising, with ideas (rather than demands) in hand.”

“Unsilencing the Writing Workshop,” by Beth Nguyen

https://lithub.com/unsilencing-the-writing-workshop/

Posted in Craft | Tagged Beth Nguyen, critique, critique groups, feedback, Literary Hub, writing workshop | 1 Comment »

I suspect this is the most frequently unasked question for visitors to this site.

A recent blog post by Erica Goss (https://ericagoss.com/2019/02/25/writing-at-a-non-writers-retreat/) describes beautifully what goes on at our monthly write-ins. Granted, we’re not at a lovely beachside house, but we are in a quiet, well-lit space set aside for us. We don’t do guided meditation, but the opportunity does exist for limited sharing and conversation.

Write-ins are a way to support each other in the most solitary aspect of our craft: the actual work of writing. Seeing another person writing can inspire us to write ourselves, and writing in the same space with others generates a kind of creative energy. Like parallel play in children, our loose awareness of what the others are doing helps us focus on our own work.

Think of a write-in as a micro-retreat, a brief period of withdrawal to cultivate the writing part of your life. If this interests you, check the schedule at the top of the page and join us.

Posted in Craft | Tagged Erica Goss, retreats, write-in, writing practice | Leave a Comment »

From the Brooklyn Poets web site:

From the Brooklyn Poets web site:

To celebrate the bicentennial of Walt Whitman’s birth on May 31, 2019, Brooklyn Poets invites you to submit a poem to our Whitman Bicentennial Poetry Contest in response to the bard’s indelible question from “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”: “What is it then between us?” Brooklyn Poet Laureate Tina Chang, Mark Doty and Rowan Ricardo Phillips will judge the contest, selecting three winners from three different age brackets: 13–17, 18–22, and 23+. First prize in each bracket will win $250; second prize $100; third prize $50. Entering the contest is free. Please submit one previously unpublished poem only. The winners and judges will read at our bicentennial celebration on May 31 and have their poems published in a commemorative chapbook.

http://brooklynpoets.org/events/whitman-bicentennial/

Read Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” here:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45470/crossing-brooklyn-ferry

Posted in Call for submissions | Tagged Brooklyn Poets, calls for submission, free writing contest, poetry contest, Walt Whitman | 1 Comment »

“Call me Ishmael.”

– Herman Melville, Moby Dick

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way—in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

– Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

Here we have two of the most famous literary first lines in the English language (and quite possibly both the shortest and longest). First lines are first impressions, and we’ve all heard that a great first line is the best way to hook readers. But a first line can also do more, as Ginger Rue points out in this post at Smack Dab in the Middle, about one of the best first lines that most people have never read but will immediately recognize.

That brings us to the point that a well-crafted first line can reach beyond the readers to connect with the wider culture. A great many people who’ve never read either Moby Dick or A Tale of Two Cities can identify those opening lines. So when you’re working on your first lines, don’t just think about how they can engage the audience; think also about how they can project what – or who – the story is truly about.

Photo by Caio Resende on Pexels.com

Posted in Craft | Tagged A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens, first line, Ginger Rue, Herman Melville, Moby Dick, Smack Dab in the Middle | Leave a Comment »